Chris Hanzsek, sound engineer, record producer, founder of C/Z Records and Reciprocal Recording is one of the most important figures in the history of this little thing everyone calls grunge. During his career now spanning over 35 years he has worked with the likes of The Melvins, Soundgarden, Green River, Malfunkshun, Skin Yard, the Fastbacks or more recently Walking Papers. Although, he is best known for his landmark compilation album Deep Six that helped form the musical genre that later became known as grunge, he’s had a complicated relationship with the record as well as with most movers and shakers of the Seattle music scene. In this exclusive, in-depth interview with Grungery, Chris Hanzsek tells the story of how Deep Six came about and why he is the only person in the world who wishes it had never happened, and he talks about the not-so-harmonious relationship he’s had with Seattle’s most famous record label, Sub Pop. Fasten your seatbelts, we’re about to take a trip down the rabbit hole of grunge.

“Defiance Has Become Art”

Let’s start with the beginning: how did you get into music? What was your motivation and inspiration?

Well, l think, first and foremost I was a fan of music. And it really hit me when I was a teenager. I suddenly discovered that sitting down and playing a record gave me a kind of a special feeling. Especially if it was an artist I just started to follow and I understood them or I seemed to understand them. My favourite records became my teachers. They gave me ideas. And they also gave me some comfort. Knowing that others were thinking the same way I was and it was nice to hear the way music put the thoughts into a spiritual form for a teenager to take that into their head. Some of my early musical interests were kind of weird, offbeat kinda things. I was listening to Simon and Garfunkel, The Moody Blues, Cat Stevens. Mostly folk artists that had a kind of a message. The Moody Blues was more of a psychedelic thing but my parents didn’t expose me to that as a kid. So, when I discovered it as a teenager, a 14-year-old or a 15-year-old, I was just totally sucked in. And I wanted more music. I wanted to check out this artist and that artist and this artist and that artist. So when I went to college, all hell broke loose. A whole bunch of kids showed up with their record collections and everyone was sharing music.

I can just picture it.

And so during the college years, I went from kind of being a musical moron to being a serious music lover and a record collector. And by the end of my college years, I had a radio show. I became a college radio guy at Pennsylvania State University. I gave myself a punk rock name. I called myself Stew Dent. My slogan (on my advertising) was “Defiance Has Become Art”. Just had a blast. And at that same time, I saw that other people were starting to play guitars and I thought that would be the coolest thing in the world. So, I was about to graduate with a well, almost a degree in theatre. I was studying acting and directing and playwriting but I wanted to just drop that and going to music. It didn’t happen overnight but I was passionate and within a year of moving to Boston I started to buy recording gear, hoping that I could become one of the people that was helping to make records. That was totally fascinating to me. I just wanted in. I started in Boston doing recording. I started out just by doing tape duplication because the people that were around me in the warehouse that I worked in they were all in rock bands.

Were you in a band as well?

No, I wasn’t in a band yet. I started getting better at guitar and I actually did play a few shows with some friends at art galleries. One of my first actual performances was in the Loft, in Boston, that was owned by guitar player named Ottmar Liebert. He is a flamenco guitarist originally from Germany. And he just moved to the US and he was in my circle of friends and he gave me the chance to perform. He told me I was one of the better improvisational guitarists he’s seen but I think he was lying. And then I just started to actually record bands in my bedroom in Boston. I recorded a few of them. My main recording gig was working for a jazz guy named David Sharpe. He went by the name D Sharpe. In his band was a guitar player named Bill Frisell. So right away I was working with some of the most brilliant modern jazz people I could ever hope to meet. And it was my first gig! So that was pretty strange. I recorded with them in my bedroom, in their basement, and in a few clubs. And then right out of the blue, I made the decision to move to Seattle, in early 1983.

Why did you choose Seattle?

Some friends that I went to college with sent me some information. They sent me some samples of Seattle music and they told me about the mountains. How beautiful it was. And they told me it was a great place to ride a bicycle or go hiking. And that I would really, really love it and they also said that the cost of living was really cheap compared to living in Boston. So, it took me about 5 minutes to decide I was moving to Seattle.

That didn’t take long.

Within two months I packed all my stuff, bought a round trip airline ticket, a really cheap one for 199 dollars. I flew across the country with the idea that maybe when I get to Seattle that’ll be a good place to really start a recording studio and maybe start a record label and see what happens. After three weeks in Seattle I still had no job so I almost used the ticket to fly back to Boston. I called to see if I could get my old job back and they said no. A week later I got a phone call asking if I would like to work in a print shop doing bindery work. The job was awful but it meant I had a reason to be in Seattle.

When was this?

It was early 1983 when I moved here, February of ‘83. It took me until January of 1984 when I opened the doors to my first actual recording studio. And that was where I started to meet Seattle bands because I didn’t really know anyone up the till then.

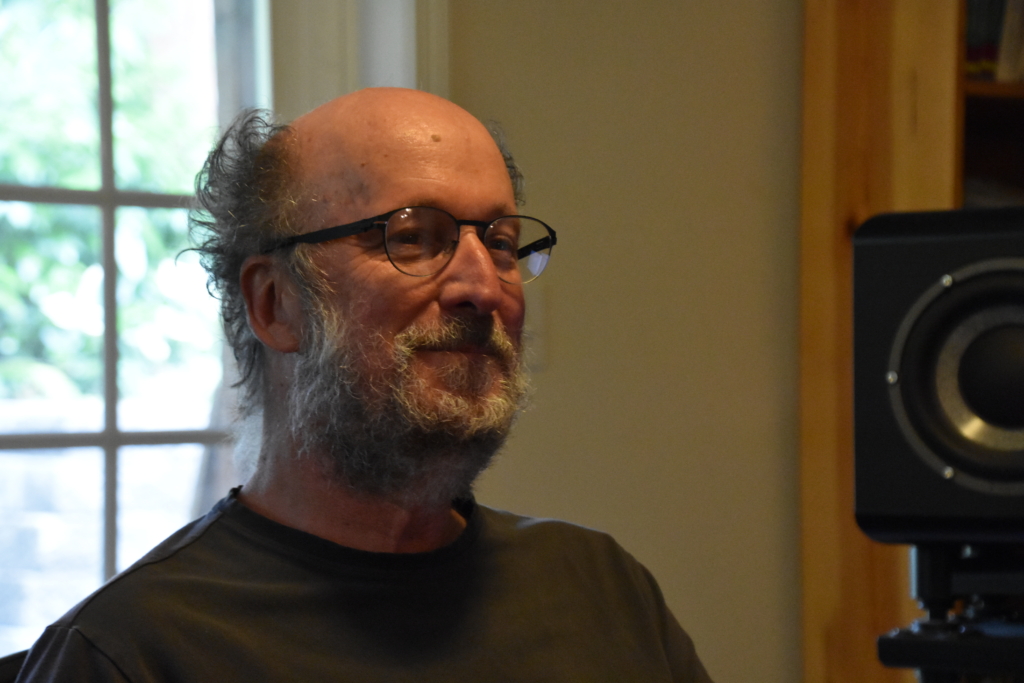

Chris Hanzsek (Photo credit: Miklós Pintér)

Chris Hanzsek (Photo credit: Miklós Pintér)

“It’s not about us, it’s about you!”

Who did you work with in the beginning?

Green River, for one. The Accused. There was a band called Bam Bam. Coven, a metal band. There were quite a few of them I can’t remember them all. Oh, there was a real punky band from Seattle: Cannibal.

Cannibal?

Yeah, look those guys up. They were early Seattle punk. So yeah, I saw a number of bands come and go. The reason I got to see so many was because, first of all, we aggressively marketed. My girlfriend was my partner at the time. Tina Casale. She’s the one I started C/Z records with. We would just walk around Seattle, all over Capitol Hill and just be just taping and stapling posters. Advertising the studio and advertising the fact that we were 10 dollars an hour. So, 10 dollars per hour to record. You can imagine…

I bet it did the trick.

A band thinking “Oh, Jeez! We could just scrape together 50 bucks and record 2 songs.” Being that dirt cheap meant that I was gonna probably meet every poor musician in town that wanted to record. And I met quite a few. We only made one year before the landlord said, “OK. That’s enough of you and all these strange looking criminals hanging out late at night. We want you to leave.” So, we got kicked out. For about little over a year, I was without an official studio and I just worked out of my home. And it was in that time that I decided “Oh well, I have nothing to do, I might as well start a record label now, too. Since I’m not busy with the studio. Seems like I should put my energy into organizing a label. Both Tina and myself thought that there was a lack of… there weren’t people putting out records and we didn’t understand why. We thought the music was good, we thought the records would sell, we thought it was the right thing to do. And we thought that if no one else is gonna do it, we want to help put out records. So, we decided “Let’s start a record label, let’s get it going and let’s see if we can become a platform for people to launch their records from. We didn’t really have big ideas about world domination or being a giant label. We just wanted to make a few and see what would happen.

What other labels were there in Seattle at that time?

There were a few. They just didn’t seem all that enthusiastic. There was one or two that established themselves but they just didn’t seem like they were moving forward. I’m not really in a position to remember the names I remember there was something called Engram records, there was one fellow putting out some interesting stuff. Like artsy stuff. I think he called it Palace of Lights… It just seemed like there was room for one more label. And especially, we were interested in rock. Hard rock, punk rock was what Tina and I had come from. I was hoping to find bands that were extremely difficult, annoying, aggressive and artsy. You know, something you might see in New York. I was hoping that maybe this town would bring forth some very challenging music. That didn’t quite happen.

What happened after you founded C/Z Records with Tina? How did the idea of the Deep Six compilation album come about?

Well, the idea was to establish the label by identifying a collection of bands and basically saying, “Here we are. Introducing C/Z Records. These are some of the bands we are interested in and this is the direction we are going.” All those six bands were slightly different. And we liked that they were slightly different because that meant that we did not have to only find bands that sounded like Soundgarden and we didn’t have to only go toward The Melvins or something. To put them all together, it was like a box of chocolates. There is a dark one here, there is one with a cherry in it there, here is one with peppermint. And then we could decide what people responded to. It was like a fishing expedition. You just say, “Six of you! Drop the lines in the water and see if anything bites”. I wrongly and naively thought it would be a good idea to be very democratic and allow everyone to have a voice about how we do things. So, not only did we let them choose the songs, we also said: ”Won’t you join us to help mix?” So, two people from every band came into the studio for the mixing. I thought that would be my way of ensuring that we would be well regarded for our ability to work as a team. Openness. Not just one dictator controlling a record label saying: “I like you, I don’t like you”. Or “I like this, I don’t like that” but rather “what would we do together?” And then, “Let’s put it on a record.” It was more challenging than I thought it would be. In hindsight, I can see that I was a little bit of a naive kid to think that that would work without becoming complicated, confusing, and counterproductive. Which it did. It became complicated and counterproductive to have as many people involved. Tina and I also thought that that would be our way of winning approval and being able to do the project in the first place. Just to say: “It’s not about us, it’s about you! Don’t worry you will be in control the whole way.” After all, we were still just two outsiders from Boston that no one knew. We both originally came from Pennsylvania, but we were from a bigger city. We had moved from Boston which was a bigger city. I think for someone in Seattle someone coming from either LA, New York or Boston might be regarded with suspicion. Because there is still an outsider coming in, maybe to do some gold digging or mining in Seattle. I don’t know if the bands all trusted us at first.

How did they approach you?

They were wary. Some maybe didn’t care, others were being very careful who they were getting involved with because none of these bands had a record out yet. We were all picking them right at the point where they were just about to go and try to do something. But they didn’t know with whom and they didn’t know what. So we came along and offered them the chance for exposure. Thinking that it would be good for Tina and I also, because we would hopefully come out of it with the reputation of: “Hey, there are two nice people that did their best to get a record label going and benefit the music community and hopefully push some careers, give them a little bit of a start.

There were a lot of bands at the time in Seattle. Why did you pick these particular groups?

I had a pair of advisers. It wasn’t that I didn’t have musical taste myself but I wanted to make sure I had a key ally, or two, helping me. In other words, again, if I was going to get the bands to come, to sign on board and say: “Yes, we will be part of your record label”, I had to make sure that I had at least one or two influential people with me. And the band that I had the most experience with, the one that I knew the best was Green River. So Mark [Arm] and Jeff [Ament] kind of were my advisors. I believe they came up with the list. They said: “We think it should be these guys”. Tina and I said: “Really? Why?” They said: “Well, we’ve seen all these guys, they are all friends of ours, they are all putting on good shows, and we think that these bands are going somewhere.” Tina and I both said: “That sounds good but we wanna meet them and listen first. We wanna hear what they have.” So one by one we had a meeting with everyone. Just to say: “Hey, we wanted to introduce ourselves and see what you’re up to and can we hear what you’ve got.” Everything went really well. We were impressed all the way around. And yeah, we decided to go with that list of six.

Were there only these six bands on the list?

Yes, it was a list of six. There wasn’t a bigger list. No one got cut.

So after the discussions, you were able to decide right away that you wanted these bands?

I didn’t do any rejecting. We just approved. After hearing some tapes and meeting people. Everyone seemed very colourful, very passionate and it just seemed just right. These bands were all different and came from different places too. We found out that The Melvins were from out by Montesano, Aberdeen area. And we knew that Malfunkshun was coming from Bainbridge Island and we knew Soundgarden, most of them lived in North Seattle. So, basically, it felt like it was just a nice collection of bands. I think Kim from Soundgarden, he is the one that came up with the name. Again, I like to let the sharing happen. You know you come up with the name, you come up with this, you come up with that. I have an old hippie brain which means that I like to try to share as much as possible and not have anyone be totally in charge.

People were showing up. These weren’t bands that were like a complete fabricated secret coming out of nowhere. They had already done that club level success. So, it wasn’t unreasonable to think that we could put it on vinyl and turn around and sell a 1000 or 2000 copies. That to us seemed very logical. But, everyone knows that compilations are hard to sell. That’s the thing. If the compilation is no good you might as well put a glass table on it and call it your furniture because it’s not gonna sell. I think what we did right was going with these six bands. They had just enough of a smouldering chemistry. Each of them, within them. There was some volatility, something about to grow, something about to explode in almost all of those bands. So, I think in hindsight it was probably a good choice to pick those six.

Yes, I agree with you.

By the way, some bands approached me afterwards and said, “Why didn’t you pick us?”

And what did you say to them?

My usual answer was, “I had no idea you existed”.

Do you have favourites on the Deep Six album? Bands or songs?

There is no any one that’s the total favourite and I certainly wouldn’t name any band that I thought was the non-favourite. Ok, I’ll name two songs that I’m most attracted to on that record. They would be, for some reason, Grinding Process by the Melvins gets me going and I also like ‘With Yo’ Heart (Not Yo’ Hands)’ by Malfunkshun. That’s kind of an interesting song. Those two give me the biggest earworms. You know the thing that gets in your head, “Oh man! I can’t get that song out of my head”. I’ve listened to it once in the last 25 years a month and a half ago; I made a tape transfer so I could give Jack two Green River songs, so he could put them on the reissues of Green River’s Dry As A Bone EP and Rehab Doll LP through Sub Pop Records. I had to take the tape and make one last transfer, one more time, to listen to. I carefully have to put it in a dehydrator, so that it will play without destroying itself. Because whenever you have a 35-year-old tape, they don’t play very well… First, you suck the water out of the tape. And then you have a week. So, I got to hear the whole tape.

Deep Six

Deep Six

This “It’s from the North-West” thing

What did you thing about that?

It still mostly makes me cringe for its unevenness and mixing issues. You know, it sounds like someone with little experience, mixed it in a hurry, in a strange studio. And then I remembered that someone with little experience, mixed it in a hurry, in a strange studio. And that made perfect sense to me. So, I’m ok with that. If I have one regret about the record it’s that I didn’t get to make it 5 years later in my career because I was still learning which ends of the microphone the sound went in. It’s hard when your whole career is judged by that one time you went into a big studio. When you were 27 years old and said, “Hey, I wonder if this is gonna work today”. You know? (Both laugh)

Yeah.

I mean people didn’t understand that 35 years later, after working with 10,000 bands on 50,000 projects, that… I’d still be here. And I’d be a mastering engineer who knows, who people come to because I have the ability to shape sound and identify problems and basically be an authority figure. I was quite the opposite back then. I was like a monkey loose in a china shop. Just throwing things around and wondering what’s going on. So, I kind of had a reverse career-dynamic happen, where the most visible thing I did happened on the second day I showed up for work. C’est la Vie.

And it’s very interesting because that was the kickoff for – let’s call it – grunge.

By the way, I’ll stop you right there. What’s your definition of grunge?

It’s a tricky question. I don’t like the term: grunge.

I don’t either. (both laugh)

I met Jack Endino and Larry Reid and they used the term: grunge. I asked the Mudhoney guys in an interview what he thought about this. Steve Turner and Mark Arm told me that they had no problem with the term “grunge”. “It’s OK for us. We have a grunge band.” But I still don’t know what the real deal about that is.

Real deal? There’s no real deal. There are only opinions. So even if there was a real thing, you’d still be left with opinions. I think grunge is a little bit like Bigfoot. Here in the United States there’s rumoured to be a giant species of man-like ape creature; 8 feet tall, about 400 pounds and it runs around in the mountains. Supposedly, he’s out there somewhere. Except when the time comes to actually get a picture or bring them back or actually find a dead one: no can do. There is no evidence. So I kinda think grunge is that way too, in that it’s rumoured to be a musical form but when you try to actually capture it and say, “Ok. It’s this”, no one will agree. So, I tend to look at it this way: Grunge was really a term used to sell records with. In other words it’s really a marketing term. It’s not an actual style but it’s a reference to a phase in the marketing of bands that came from a certain region. Ok. So, that’s not very flattering, is it? That it was just used to sell records but that’s kinda my thought process there. If someone put a gun to my head though and said, “Tell me, what makes a grunge band? “, Most of the definitions I hear is something along the lines of: “Well, it’s based on guitar tone first and foremost.” It’s got some form of a shrieky vocal or a “yarly” vocal. In other words,”YAAAAR!” (He imitates.) You either have to go Pearl Jam or you have to go Soundgarden or somewhere in between. I always thought Soundgarden was just a kind of a modification of Led Zeppelin with a little twist on the guitar tone and some different tempos. But, that’s just me.

We’re not any closer to knowing what it is…

Yeah. Honestly, though, I think… the grunge term was a very loose thing and I don’t think it’s an official genre. I don’t even think that it’s an official subgenre, because you really can’t cleanly identify, “Ok. Here is a line where something is and here is a line where something isn’t”. Over time, I can see that some people have been admitted into the grunge club that didn’t sound grunge, and others kinda sounded grunge that weren’t admitted into the grunge club. And then, I can see that others from outside the region have been admitted into the grunge club. So, obviously that destroyed the whole “It’s from the North-West” thing. You had your Stone Temple Pilots and Bush…

I don’t think they are grunge.

They kinda sounded like Seattle bands. They kind of morphed into that. So, I’m still waiting for a really good definition of grunge. I don’t think it exists. There was once this Metal Evolution TV show on VH1. They came to town about 10 years ago and they interviewed all the people in town. They even interviewed me too. But I ruined everything for them when they asked me, “Ok. Now we wanna know from you: Is grunge metal or not?” And I said, “Well, first of all I don’t think grunge is anything and secondly, I don’t think it’s metal either.” Basically, they left, they said thank you very much and then my interview was nowhere in the show at all.

Figures.

Yeah. I said all the wrong things. They wanted things that supported their story and I kept saying dumb stuff that didn’t support their story at all. Being a little bit of a contrarian, I was a narrative wrecker. They looked at the footage, “This doesn’t fit anywhere. Can him!” So, I got canned.

But something had started with Deep Six. These bands got on their way up. And for example, it was Soundgarden’s first release.

The reason all of those bands were successful is because they were enthusiastic musicians. Their hearts were in it. They found the sweet spot. They found that little place that a lot of America wanted to go and no one knew. Half this country wanted to rock out to Nirvana and no one knew it. We’d been through some rock experiments; we’d seen the LA production machine doing certain things. I don’t know who was popular back then. Who was popular in the mid-80s? I don’t even remember. There were metal bands. Lot of new wave bands, you know, synth-pop and things like that. Punk rock, itself, was still kinda hopping along in various parts of the country. This part of the country seemed to say, “You know what? We’re gonna give you a kind of a punk rock but we’re gonna throw in heavy dose of metal and we’re gonna also simplify it a little bit.” Punk rock threw away a lot of the requirements to be a professional musician. So did this – let’s call it – the Northwest musical movement. It threw away some of that requirement to sound like either progressive rock or polished pop. You know a lot of times music places a barrier on its creation because everyone else is doing something so slick, that unless you have the money to match that production value, you don’t bother. Why compete with Yes if you only have four-track recorder? It’s not going to work. You’re gonna need more tracks and you’re gonna need more time. So this grunge or this Northwest music movement was also very much a low budget permission to make music. Just like the punk rock phase. When I heard the Ramones, I wanted to go buy guitar so bad. It was like, “Shoot, yeah! I can do that!” They sounded like they were having so much fun and I wanted to be a guy that didn’t have to go to a music school and could still express myself. And that’s what caught hold in this area. We really started to have a tradition of kids going to junior high school and maybe playing in the high school band. They started listening to music, they got into high school, they bought instruments, they got out of high school, and they put out a record. It was like 1, 2, 3.

What happened to you and C/Z Records after the release of Deep Six?

C/Z Records continued on after I decided to back away from the record industry. The experience of the Deep Six compilation, making it and also the experience of trying to sell the records and gain distribution and deal with the distributors… All of that wore me down a bit. And, I was doing it alone at that point. Tina wanted out, right in the middle of the production process of deep six. We’d always had issues. You know boyfriend girlfriend issues.

I see.

But when we tried to do something of this magnitude, the pressure was too much. And she quite unexpectedly, just sort of called it quits in the middle of the recording sessions. She had an argument with the guys from Green River. I can’t remember what it was about. I don’t wanna necessarily say it was her fault but between the two of them they were having a loud non-harmonious discussion that resulted in kind of a split. And the split was between the scene and us. So, I think I lost my job in the recording industry that evening. (laughs) So that compounded with the fact that when the record did come out, no money at all was put into advertising. It was just like, “Oops! Here we are! “. I think we handed out records to all the bands, like, “Here is your 10 copies!”, or whatever it was. I don’t remember what it was. Almost immediately I started to hear rumours that, “Hey! Everyone’s not happy with you because you’re not putting any money into promoting this.” And my response was: “Well, Tina had the money and she moved back to Pittsburgh.” I had a day job running a printing press and that place went out of business just before the record came out. So they said, “Sorry! You’re out of the job!” So I had no job, I had no girlfriend and now I was hearing that everyone was not liking me anymore. My reaction was: “Really? Screw you all!” You know. I was mad. In a way, I almost didn’t want to advertise it. I almost wanted to just say, “Hey! Fuck you! Advertise your own record!” I never said that and there were never any conversations between me and anyone. I almost had some re-considerations. I decided, “Well, you know what? Not everyone in this crew is gonna be friends with me, I’m not gonna be friends with everyone, so maybe I’ll just try to focus on one or two bands that I like. I immediately went after the Melvins and said: “Let’s do a record!” Just me and you. Let’s make it really quick. I think we can record it live write to tape. No mixing. Just hook it all up, make it go right to two-tracks and then, I’ll walk out with the two-track tape and we’ll press a seven-inch. I saw that as one last way I might be able to get a record going, to improve my reputation a little bit. I got to C/Z002 with the Melvins and put that record out. I think that probably happened just a few months after Deep Six that I got that one going. It was difficult to promote that because all of a sudden I didn’t seem to have anyone in Seattle willing to give me even a review on it. Whereas Deep Six got a huge review in the Rocket magazine. Bruce Pavitt wrote it.

What did he write?

In giant headlines this big, he said: “THIS IS IT!” Exclamation mark. And then a beautiful article about how… “The world is going to be so surprised! This is wonderful! Finally, a collection of bands that really strikes a chord. They’re gonna be amazing!” I said: “Yes! Yes! The local press is on our side.” I had it in the back of my mind that what a great guy Bruce must be… Anyway… So, I immediately sent him the Melvins record again, right? And then: nothing. And then a month later: nothing. Then a month later: nothing. That’s funny. He must have lost it. Maybe someone stole it. Maybe he didn’t like it. The record came out in April and then in August I finally saw a little review in the Rocket magazine and it basically blasted it. It said, “This is a really poor recording. It’s weak and thin and lame. It’s a shame because the Melvins are a good band. Hopefully, they’ll find someone to record with. They can actually do a good job.” Or something along that line. And then, within a week I think I heard from someone else that Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan [Poneman] just started a record label. So I said, “Oh!” So, that was my signal. That and the fact that they called me up one day and they said: “We wanna meet with you.” And I thought, “Oh good, good! Maybe they wanna join forces. Maybe they want to hire me.”

Like an employee or…?

Yeah or something. Maybe they thought, “Let’s get everyone together and form one big label and have everyone work under the same umbrella.” I forget exactly when that was. It must have been sometime in ‘86 or ‘87. They said, “Well yeah. Let’s meet. We’re starting a record label, we have an office.” I said, “I know, I know, I’ll come meet you!” So I went in and Jonathan just sat down, started talking to me and Bruce was working on the cover to the Green River album. Their first release. He was just laying it out on the floor. And Jonathan said: “So are you still in the label business?” I said: “No! Where did you hear that?” “Cuz I just wanted to know…” I said, “No, I’m not, why?” “I just wanted to know. That’s all.” I said, “Oh, that’s all?” So, then I went home.

Nice meeting.

Had I said yes, there might have been some more meetings going on but because I said no, I’m not interested in the label business then they sent me on my way. From that point on then we kind of hardened into a “Sub Pop doesn’t like Chris, Chris doesn’t like Sub Pop” thing. Because, as luck would have it, my studio was where Jack [Endino] and I were working…

Was that Reciprocal?

Let’s call it Reciprocal version #2, because I didn’t know Jack prior to Deep Six. I met him during the Deep Six process. The previous location was also called Reciprocal Recording.

Chris Hanzsek (Photo credit: Miklós Pintér)

Chris Hanzsek (Photo credit: Miklós Pintér)

“To survive in the music industry as long as Jack Endino and I have, you really have to love what you do.”

How did you meet Jack?

I first met him as a musician. He was one of the ones that came along to help with the mixing. You know, from Skin Yard. And so conversations happened like, “Who are you?” “Oh, I’m Jack, I also like to record.” So, Jack and I started Reciprocal Recording version #2, because he was the one that found the vacant space where a studio had been. And he said to me, “I’ll tell you where the space is if you let me be your partner.” I said, “Yeah, yeah. Of course. You can be my partner. That’s fine.” So we started at being partners and then within a month or two he realized he really didn’t want to be a partner, he wanted to be a producer. He didn’t want to be a studio owner. So, at that point we made a division of labour happen, where I would be the guy that bought the equipment, collected it, and ran the business and looked after the day-to-day operations. He would be more of an independent producer guy – less obligation. That was fine with me because at that point in my life I was just about to get married, just about to have kids and I really wasn’t all that interested in the volatility of the music industry. Zooming all around, going to different studios, record labels and things like that. I just decided that the best place for me would be just to work inside one building and just be a guy who wasn’t in politics, but was just an engineer. I consciously decided that I wasn’t going to compete with Jack, as much as I would be complementary to him. I would be the backbone that made the studio happen, that worked the acoustics, that bought the gear that resolved the issues, that did the troubleshooting, that paid the bills, all that other stuff. And a guy like him, and others would get to be the name on the record, so to speak. That didn’t mean that I wasn’t an engineer – because when you’re a studio owner, you’re also an engineer – but you end up working with whoever wants to work in your studio. You don’t end up picking and choosing based on the sound. Jack went about his career trying to pick and choose as much as possible for things that he liked and wanted to work with. I, on the other hand, heard the doorbell ring, saw the money and said yes. (laughs)

We were at a Derelicts/Blood Circus/Swallow show in August and Jack was there as well. There was a very friendly communication going on between the two of you, which was great to hear. I know you’ve worked on a lot of projects together, lately, on the Walking Papers album – just to name one of my favourites.

Just in the last 10 or 12 years I’ve been doing almost exclusively mastering work. He tends to try to do everything himself but he also realises that sometimes it’s better to let someone else also in on it, so that you don’t end up having too much tunnel vision working on your own things. Sometimes when you get that second opinion your work gets stronger because you have another set of ears and another set of eyes looking at it. So, the last 10 years or so we functioned in a way where a lot of our interactions are mixing, he hands it to me and then I just do the final touch to master it. Do you know what mastering is, by the way?

Yes, of course.

Ok. It’s like going all the way to the moon and then getting someone to finally land the spacecraft very gently on the moon, on a certain spot. Just have to be very delicate and have everything in mind and kinda have an eye on the big picture. We’ve maintained a cordial relationship for 33 years. There have been times when he was really, really pissed at me probably, you know, really angry; and there have been times when I’ve been the same. Sometimes justified, sometimes it’s probably in our heads. But I think overall, we both understand that we’ve both been beneficial to each other. And going back before 10 years ago, you know, the previous 10 or 20 years… How much business he brought to my studio and how much of that went to my bank account is pretty considerable. So, for me to say bad things about him at this point would be irresponsible. (laughs) If you follow me… In other words, I’m grateful for the business that he’s given me, even if we haven’t always seen eye-to-eye on every issue. We’re both grumpy old men, so we can sometimes annoy each other with our own grumpiness. But we wake up the next day and come to our senses.

As far as I can tell, while Jack and you are not the easiest guys to work with, you are both warm-hearted, open, and kind people.

That is the miracle! Because the music industry can really make you either very hard, very cynical, very mean, very ugly… or very gone. It’s not an easy business to stay a nice guy in. It takes work. It’s a lot like a marriage because you marry someone, and for a little while they are the most beautiful thing you ever knew; but then once you figure out that there’s hair growing in funny places, and there’s warts, and there is bad tempers, and there is excess drinking and not everyone is super nice to you. And the money is not the kind of money, where you think, “Oh this is such good money, I’ll put up with anything”. No, you won’t. You really have to be dedicated. To survive in the music industry as long as Jack and I have, you really have to love what you do. For more reasons than just one.

You worked on a lot of records in the past decades. Can you recommend a few of them that you especially liked?

I worked on a lot of special things. It’s hard to be fair to everyone and name just one or a few because if I name one thing, 10 minutes later I’m going to think of something else. And then 10 minutes later I’m going to think of something else.

Ok, can you name 10 then? Other than “The Big Four?”

“The Big Four?” Let me see if I can name them: Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Nirvana.

That’s right. And for a lot of people that’s the end of story when it comes to bands from Seattle. Some might include Mudhoney, Screaming Trees or The Melvins… But there are so many other great bands out here. We were at that show at Parliament Tavern. Blood Circus was amazing! One of the greatest shows I’ve ever seen. Or The Derelicts. They were extremely powerful!

Yeah. Those guys are good. I was really struck with the backline. Everyone in the band just seems to be playing like it was a high school band rehearsal. But the singer had definitely the star quality, working-the-crowd type thing going on. He understood how to be a person with the microphone in the room. Not everybody knows how to do that. Some people think it’s just to hang on to the mic-stand and just let it pick up sound occasionally. Other people, they’ve seen Wayne Newton and they were gonna improve on it. They really know how to work it. Jeff Angell is a prime example of someone who can work a microphone. Sometimes you just want him to stop playing and show you some more moves.

Right.

I was going to ask you! What did you mostly like about Blood Circus? What was the appeal?

I don’t know. There was a special groove in their music. I did not really concentrate on the lyrics, but the groove in the music – the drummer, the bass player, the guitarists were great. I also like Michael Anderson’s voice but the show itself was a trip. I just talk about it and I get goosebumps.

I get those too. I often show people. I say, “Watch what this song does to me!” When the song comes on, I go, “Watch this!” Four chords can go by and then… Goosebumps!

“I have faith in guys like Jeff Angell”

Same here. From all the records you mastered last year, my favourite one was Walking Papers’ second album.

I’m captivated by much of the Walking Papers material. I have my reasons when I listen to it. I played that album for other people and they shut it off in the middle. So, it does not appeal to everyone.

I can’t comprehend that.

I think for some people they are not ready for the explorations that are being made. In other words, when you make an album you can learn to work doing things that have been proven to work; but if you constantly refer to things that have been proven to work you make an incredibly boring album that sounds like everyone else’s album. And when there is absolutely nothing new, it can be completely forgettable because there’s no reason to remember it. Now, when you take a chance, when you say, “No one has ever done this before. I wonder if someone might like this, the first time they hear it.” Sometimes yes, sometimes no. You’re taking a risk. If you take one or two little risks, and then make everything else the same: that’s your typical album. If you take a whole lot of risks and very little resembles the other albums, then you’re taking a big risk. Taking a big risk can either result in you being a genius who’s ahead of your time or it can result in the last record you will ever make, because no one wants to help you make a record again. So, everybody works that line between the known and the unknown. The risk and the no-risk. I think a band like Walking Papers, for instance, tends to try to always wanna stay on the more risk side. They are just not comfortable being on the predictable side. It just kinda comes down to: “Can you find that sweet spot? Can you be the one to make the music that everyone is about to want to hear?” If the answer is yes, then you’re good to go. I don’t know what the band is up to. They’ve been experimenting with different players on the recent tour. I’m not sure what they’ll become in the future. Whether it will stay that way or weather Duff [McKagan] will get tired of Guns N’ Roses or this or that. I don’t know what will happen. But I have faith in guys like Jeff, just because I admire his risk taking, I admire the fact that he’s persevered this long too. I remember working with him 20 years ago and thinking, “Hey! You’re a good musician!” But I didn’t see anything special back then. But starting about 5 years ago, I started seeing something really special. So, hopefully it goes.

Did all the members come here to check their sound while you were working on the album?

Everybody’s been here but Duff, I think. Barrett’s been here a lot. I’ve worked on Barrett’s solo records, as well as a couple of other records that Barrett’s been involved with. Barrett likes to be hands on. He doesn’t just send me files, he likes to show up so that he can see what’s going on. He likes to get involved.

Which is easier for you when you work: having somebody over from the bands or doing it alone, being able to focus on the project more?

It can go either way. Sometimes having a musician work with me gives me a secret insight into what they really like. What they really desire, what really works well for them. And if they are not a super verbal person or not good with written skills, then it’s sometimes just a great thing to be able to see their reaction and understand just by watching body language, that this is a good thing, and that’s not a good thing, and it can help me give them exactly what they want. Other times, maybe they get in their own way, they slow me down, they can distract me, they can give me conflicting information or they can insist on something that doesn’t make any sense and I can’t stop them. So, sometimes I do work better without someone looking over my shoulder. It also depends on how much I already know what they want. If I worked with someone before and we’ve been through the process, then I kind of know already and they don’t need to be here, they don’t even need to say a thing. They can just hand me files, they can give me a list of what order to put the songs in and I will just know. I know what they like based on my experience. They don’t have to say much, I just guess exactly what they want. They like that. People like it when they don’t have to go through a long process of finally getting to the resolve of what they actually wanted in the first place. Musicians always want the engineer to kind of know in their head ahead of time what it is.

What are you working on these days?

Sometimes, I will work on 10 or 12 different projects a week. Not the whole thing. Sometimes, it just a small piece of something. Sometimes, I make a master and three weeks later someone says, “Oh! We need you to adjust one song.” So, then my work that day is, I adjust one song and I send it back. It’s more of an in-and-out file-buffing shop, where I don’t just start on a project and then 6 weeks later I finish. It’s more like a little bit of this, a little bit of that. The bigger project consumes my time. If someone hands me a nice big album and says, “Take your time with it!” that might occupy 2 or 3 days, for a portion of each day. I will often only work a certain number of hours per day, because the ears tend to have a daily limit. After 3 or 4 hours, when they get tired, I stop, so I don’t make a mess. And I come back and I see what fresh ears tell me again the next day. So, if someone lets me have 2 or 3 days, I’ll listen to their project over 2 or 3 days, just to see if it doesn’t strike me differently, when I wake up on Tuesday, instead of Wednesday or whatever. What am I working on?

Oh my god!

A lot of these are from South America. Yes. I ended up working with a lot of bands from Brazil, Chile and Argentina.

How come?

Jack knows why it happened. He introduced me to a Brazilian band or two, about 10 or 15 years ago. I probably started with Nando Reis. And then, another project came along about 10 years ago. A band called Far from Alaska. I have a lot of work from Brazil. But I don’t argue with that. I look at it this way: maybe Seattle isn’t crazy about old Chris Hanzsek, but South America loves him. I have some clients in Europe. In the UK. I’ve worked with some people in Ireland, Bulgaria. You stick around long enough and because of the internet, the world is your playground.

Absolutely.

I try to communicate well, I try to be a good business person, and I try to be fair. By having a good reputation, it keeps me meeting new people.

Chris Hanzsek (Photo credit: Miklós Pintér)

Chris Hanzsek (Photo credit: Miklós Pintér)

“I’m about the only one who wishes it never happened.”

You started off being a record producer, and started a label. Yet, since 1986, you hardly go near that. Why is that?

Sometimes people say to me, “Oh yeah! You’re a record producer!” And I go, “What are you talking about?” I don’t consciously try to run around producing records. Now, that doesn’t mean that I didn’t, or don’t. It just means that I just don’t pursue that. This is important. I’m much more proud of working on 5 to 10,000 projects, than I am of working on any one. To give support to many, many people, year, after year, after year; rather than just being involved with a couple of bands in one year. It’s been a long run and I’m proud to have made it this far. If anyone says to me, “Oh! I appreciate you because you did Deep Six, and you worked with those six bands and you helped them getting started!” I go, “Yeah, that was good but they would have done that without me. They’d have been fine. They were good bands. I didn’t really make them. That’s not a real trophy. That’s just kind of an: “I was there when the UFO landed.” Did I make the UFO land? No, I didn’t. I just happened to be there. That’s not to say that my energy didn’t help, or my positivity didn’t help. That my ideas didn’t help. Of course they did.

But the Deep Six album did help put you on rock music’s map.

I’m about the only one who wishes it never happened. (both laugh)

Without it we never would have met!

In hindsight, I think if you get all those people together, everyone on the record, that’s still alive, I think they’d say thanks. And that they’d say, “Oops, sorry about trashing you.” Because for a while I had the sense that Sub Pop and the majority of the bands had kind of come together and said, “That dude! That dude is a real fuckup! Let’s do it right. Let’s do it our way.” And so there was a conscious decision by a collection of people to move away from anything I was involved with. Now, the fact that I owned a studio that kept me hanging around. Perhaps, uncomfortably. And, I kept hanging around long enough that the stigma started to wear off. Once we got to 1992, and Pearl Jam was selling a bazillion records, and Soundgarden was about to sell a bazillion records, and Nirvana was already selling a bazillion records… I think all was forgiven at that point. But for a while I was definitely the guy to avoid. It was obnoxious, because I was owning a studio and then finding bands that I once worked with, going around, to make sure they didn’t run into me. You know that kind of thing. So I just settled in as the studio-owning Black Sheep of Grunge. But, I did believe that I could wear through it and that it would go away eventually. And it did. But, it had enough of an impact that caused a major career shift on my part. Not entirely unwarranted. When I look back at the way Tina and I performed, I think to myself, “We weren’t best. We weren’t making the best attempt. It could have gone better.”

Anyway. Jack kind of middle-manned this entire way. He was Sub Pop’s man and I was the anti-Sub Pop. Jack is right in the middle, Sub Pop’s over here, I’m over here. I own the studio, where Jack is doing all the work for Sub Pop. And Sub Pop, back in the early days, they were about the baddest people in the world, when it came to doing business. They were like kids in the candy store, who thought that the world owed them everything and that the world would bend over backwards to do anything. Well, I was Mr. Pissed as Hell, studio owner, and when they owed me money, I said, “Pay up, or you’re not doing anything here!” And then they would just look at me, like, “Oh, you asshole!” Jack would be the guy in the middle. I was bad cop, and Jack was good cop.

So, Jack wanted them to pay too, because that was where his money would come from. We were making a living by charging people $15 an hour. Pay all the bills, and whatever is left over, that was our food money. Right? We needed the money, so when guys came along, like Sub Pop, and said, “Hey, spend the half month recording and then watch us flake off, because we have no money!”, we’d say, “No, no, no. You have to be honest and you have to be up and up about it!” It wasn’t just my studio, it was in everybody studio. Now, that said, after they went through the first however many years it was… the early years, to the point right up where they were about to die. Then, they sold whatever it was. You know, they sold Nirvana, I guess, and probably made enough money to resurrect again. And these days, I’m sure they’re just wonderful people to do business with. And I do business with Sub Pop occasionally, and they are very good. So you see it was all: the past.

Let bygones be bygones.

Yes. But you be apprised of the fact that back then they were pretty nasty assholes, you wouldn’t have wanted anything to do with, nor would I. And I was the guy who didn’t play their game. Never got to be their favourite dude. Probably, if I ever got together with Jonathan or somebody, we’d probably be friends. It’s just we never had that healing process. They just dumped dirt on me and I just stuck my tongue out at them. That was that.

Difficult story.

You know what? All’s well that ends well. Let me not complain too much, because I got to have a career to this point. It’s not paying me a lot of money right now and I’m actually thinking I might wanna do something else, but it’s been something I wouldn’t trade away for anything. Just the ability to be interacting and working with artists, musicians. Just feeling all of that… everything: the positivity, the creativity, the risk. There is no reason to want to do anything else. Except now maybe I want to do something else because the music economy is really depressed. There is not as much money in it. Also, I’ve done this for so long. I really like adventure and the adventure in this is going down. I’m at a low spot in terms of feeling like I’m breaking new ground. That’s why I’m going to Hungary where my family originally comes from! Adventure!

__

Read more:

Jack Endino: This was something new, since prior to that everything in Seattle had been indie rock

Toni Wood: Andy loved the sparkle he put in people’s eyes

Jeff Angell: Walking Papers has an address on the main street

Jeff Angell: I’m kind of Ian Astbury’s illegitimate child

John Evans: There is nothing to me like Pearl Jam

Mary Reber: We had no idea that this is going to be the finale of Twin Peaks